Entering the mood-lit cafeteria-turned-dance floor, I ducked under the hanging crepe paper to the relative safety and anonymity of a dark corner. I scanned the room. It was mostly jocks, cheerleaders, and an assortment of other popular people. No one I actually knew. They were paired up or in groups, laughing and joking. It took all of 5 minutes to realize I didn’t belong.

Three decades later, it’s a memory so vivid I could almost smell Old Spice on polyester and the residual scent of just-smoked weed. “Steve – is one of your classmates looking for you?” I managed a smile as I deleted the email. If those brainniacs at Classmates.com only knew how ridiculous their emails sounded to me. I was so not popular in high school. It’s not that I was unpopular; that implies people didn’t like me. No one really knew me well enough to not like me. I was pretty much invisible.

Having completed my freshman year without so much as a No. 2 pencil mark on my social calendar, I wasn’t really looking forward to my sophomore year. In a first- and last-ditch effort to make a name for myself, I decided to attend the Homecoming dance. Those tacky, glitter-filled posters lining the halls promised fun, friends, and a night to remember. I would achieve only one of the three.

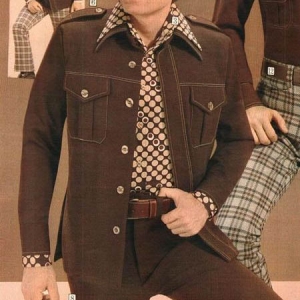

The weekend before the dance I spent an entire day canvassing the local mall looking for the perfect coming-out-of-my-shell ensemble. Not having a date to help, or friends to stop me, I walked out with 100% polyester-poplin blend, turd-brown bell-bottoms, a matching jacket and a slippery, shiny poly-blend disco shirt. Oh, and cowboy boots.

That night I told my mom I was meeting friends at the dance and made her drop me off a few blocks from the school. I walked across the parking lot and stood in the shadow of a giant pine tree, watching for anyone I knew; or more accurately, anyone who knew me. Soon it was too dark to see who was arriving, so I made my entrance, fittingly, in the same way I would spend the rest of the evening, alone.

Feeling miles out if my element, I ventured away from my corner only a couple times to refill my soda. The air had become thick from dancing bodies and fake fog. I set my suit jacket on an empty lunchroom chair. Whoever said “Showing up is 80% of life,” was never a bystander at his own homecoming dance.

I glanced at my watch again, 10:55. I’d leave in another half hour, if . . . if what? I didn’t know what I was expecting. Across the room, I locked eyes briefly with a girl in a long white dress. I sort of knew her. Our parents were friends and I had been to her house once in grade school. Tall and skinny with glasses, she had burnt-orange hair, skin the color of Wonder bread, and freckles from tip to toe. She reminded me of Sissy Spacek in “Carrie.”

Each time I accidentally glanced in her direction, she was looking in mine. Did she recognize me? After a few minutes, I snuck another look, she was gone. I was relieved . . . until she tapped my arm. I turned to her and she smiled, “Do you want to dance?” My twisted logic said dancing with “Carrie” would be more embarrassing than standing alone in the corner all night. I turned to her and smiled nervously, “No, thanks,” my voice cracked. The reply must have taken a second to sink in because she was still smiling as I turned away. I wasn’t sure what else to do. A few seconds later I turned back around, without anything to say, but she had already started walking away. All I could feel was relief. In that moment, I saw so clearly what, up to that point, I had refused to admit and would still take years more to accept.

I grabbed my jacket. Exiting through the glass doors to the patio and into the cool October night, I walked unnoticed through the crowd outside. I picked up pace across the grass and through the parking lot, the sounds of music and laughter fading until all I could hear were my boots on the cold asphalt. I felt the warm tears start to spill down my cheeks. There were a million thoughts going through my head and not one of them good. I cut across the horse field as the tears turned to sobs. At one point I tripped over a rock or stump, almost catching my balance just before hitting the ground. I yelled out at nothing and no one. The rest of the night was a blur. I made it home, muddy from the field, but in one piece. I lied to my mother “great time, danced . . . “

I chose not to speak of that night again until about 15 years later when I was out to dinner with the guy who would later become my life partner. We were at a small divey Cuban restaurant in Los Angeles, seated by a window, the neon sign casting a red hue on names crudely carved into the wooden table. Nervously tracing the letters with my fingers, I replayed the events from that night. He sat in a focused silence through the whole story. I could tell he understood my pain, but oddly enough I sensed no pity.

And then it came up again, just the other day, after my latest trip down that unpaved and pot-holed memory lane. Damon, the man I’d shared 21 truly magical years with, sensed my mood. “What’s wrong?” he asked. “Nothing really,” I said, “I was just thinking about, um . . . do you remember that story I told you years ago about my high school homecoming dance?” He flashed a knowing smile, his eyes darting to the floor before settling again on mine. “Of course,” he said, “it’s what made me fall in love with you.”